There are plenty of guidelines and instructions on implementing a deviation system in a pharmaceutical/medical device company. However, there is a big difference between theory and practice when it comes to handling deviations and keeping oversight. Save yourself valuable time by implementing ideas presented in this blog on deviations and avoiding common pitfalls. Taking the regular deviation workflow as basis, we provide recommendations derived from many years of experience with both smooth-running systems and companies struggling with their deviation workload.

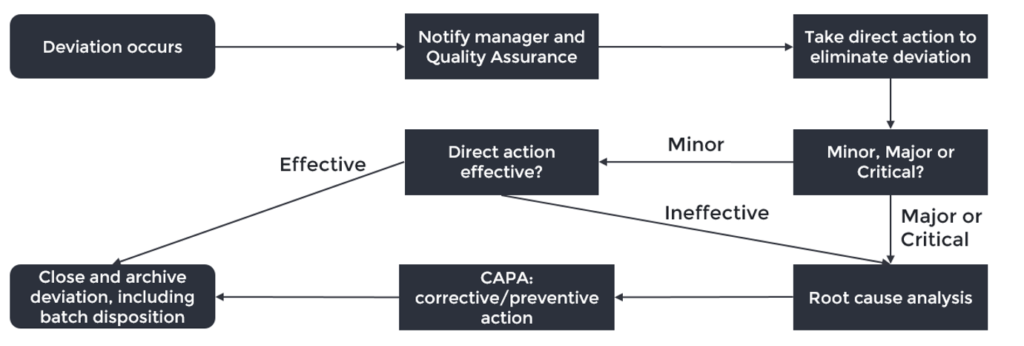

We will use the scheme below to guide us through the deviation workflow and highlight the points where you can make the difference in your company.

- Deviation occurs: not every error or event is a deviation, learn to recognise when it is. If the event is likely to occur on a regular basis, define your procedure in a way that (1) detects the event, (2) corrects mistakes and (3) assures the quality of the product. For example, small mistakes in a batch record can often easily be remediated by correcting it and adding a comment. However, do not use this as an excuse to file fewer deviations.

- Notify manager and QA: most deviations will be noticed by operators working with the product or materials. It is important to have a company culture where reporting deviations is stimulated, even if you made a mistake yourself, otherwise patient safety may be impaired.

- Correction: take action to eliminate the deviation and document what is done and how, which can be used as a reference if the deviation should recur in the future.

- Manager and QA assess the risk and determine the criticality: a common way to rate deviations is establishing the (1) severity to patient health/safety, (2) probability of an adverse event taking place and (3) the detectability of the deviation. The risk becomes higher with higher severity, higher probability and lower detectability.

- Root cause analysis: what really caused the deviation? Try to look beyond human error, but use tools like 5xWhy and a Fishbone Diagram to dig out the root cause. More importantly: understand when to use which tool. A Fishbone Diagram is useful for complex deviations, whereas 5xWhy is suitable for less elaborate situations. This will help defining a solution which increases the robustness of your process and decreases the chance of recurrence. A proper root cause analysis will help you understand the problem and is therefore the most important step to prevent recurrence of the deviation.

- Corrective/preventive action (CAPA): make sure it does not happen again. A corrective action eliminates the root cause found in the root cause analysis. An effective corrective action will reduce the chance of recurrence to an acceptable level, though it is often hard to prevent recurrence with 100% certainty. Balance the time and effort put into a corrective action with the risk of recurrence and severity of the deviation.

A preventive action eliminates the root cause of a potential problem. Based on what happened, you may be able to identify other risks in your process that have not yet occurred, but can already be addressed. - Close and archive deviation: no batch should leave the company whilst a related deviation is still under investigation. The deviation report should be clear enough to be understood by another employee than the author at least until the expiration date of the batch, so that complaints from the market can be investigated if they should be filed.

Clearly, the proper handling of deviations and CAPAs requires one or more systems to be in place. The Quality Assurance department is owner of this system and responsible for assigning owners to deviations and keeping track of deadlines. This should be a daily or weekly routine to prevent build-up of a backlog.

Take care to design your system and train your personnel to prevent these common pitfalls:

- Creating a backlog: How many times have you heard (or used) the excuse that there is no time to do something? Deviations require lots of time to handle properly, make sure this time is available, lest the amount of open deviations becomes larger and harder to manage. An effective method may be: when someone has missed their deadline, they need to report this on paper to the Quality Director or CEO with a justification (this may sound like a juvenile rule, but it definitely works).

- Missing deadlines:

- Reporting of deviations – do not wait several days before reporting a deviation, lest you forget important details

- Investigations – the process outlined above may require a lot of time, do not procrastinate the investigation, but start right away when details are fresh in everyone’s memories

- Closing deviations – once the investigation is complete, do not wait with making decisions. Again, it becomes harder to remember what it was all about the longer you wait.

- CAPAs – define realistic deadlines for the implementation of CAPAs, shorter is preferable to longer. Clearly describing a CAPA is essential to later be able to determine whether it was effective, especially when the author leaves the company and a colleague performs the effectiveness check.

- Extending deadlines – when a deadline is missed, ask yourself if there is any point in extending the deadline. Instead, why not honestly mark the deviation as overdue and assess the risk of not taking action immediately. Extending a deadline does not solve the deviation and may make overdue items invisible.

This blog is densely packed with recommendations beyond the basics of deviations and should help you refine your company processes. If you do not wish to reinvent the wheel or you would just like to learn more about effectively managing deviations, reach out to us and profit from our many years of experience.

Interested in learning more? Contact us today to find out how we can help with your global regulatory needs

TAGS: Compliance Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA) Life Science Consulting