March 26, 2015

March 26, 2015

A recent analysis by the Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development places the price tag of bringing a new drug to market at around $2.6 billion. The reason for this is simple: failure. Drugs can, and do, fail at every stage in the pipeline. While a certain percentage of drugs are expected to fail during development, when companies reach the NDA filing stage, it is the hope that the application will be approved. Despite this, an FDA-sponsored study reported that about 50% of new drug applications (NDAs) were not approved upon their first submission, while 73.5% of NDAs ultimately approved (after one or more submissions). This data reflects drug applications for new chemical entities (NCEs), which are drugs with an active ingredient that has not been previously approved by the FDA. This study, in addition to another JAMA study, can offer valuable insights for companies looking for ways to ensure their drug approval process goes as smoothly as possible. It would be wise for sponsors to review these studies and work with their regulatory staff or external regulatory consultants to ensure that their new drug does not suffer the same setbacks.

The first study, titled "Scientific and Regulatory Reasons for Delay and Denial of FDA Approval of Initial Applications for New Drugs, 2000-2012," reviewed the reasons for delay and denial of new drug applications. Of the applications that did not receive initial approval, deficiencies in safety and efficacy were the most prevalent, and there was a median delay of 435 days for those who eventually gained FDA approval. The most common efficacy concern was dosing, which is usually determined very early in the process and therefore not often experimented with during Phase III trials. A regulatory strategy that incorporates dose-finding into later stages of development could have avoided this problem. Increased communication between the sponsor and FDA, as well as a better understanding of what FDA is looking for, can increase the chance that the sponsor's application will be approved upon the initial submission. The takeaway from this study is clear: the benefits of a well thought out regulatory strategy, even at the earliest stages of drug development, cannot be overestimated.

The other JAMA study, titled "Clinical Trial Evidence Supporting FDA Approval of Novel Therapeutic Agents, 2005-2012," analyzed the evidence from 448 pivotal efficacy trials for 206 indications of 188 novel therapeutic entities. The study found that the quality of evidence required for approval varied widely, with cancer drugs having the loosest requirements for approval, as a majority of new cancer treatments had only one pivotal study. Other study highlights include the discovery that only 54% of the trials for drugs with an orphan designation were randomized, which sharply contrasts to almost 95% for drugs without an orphan designation. In addition, it was found that 95% of trials used surrogate endpoints for drugs obtaining accelerated approval. This paper reaffirms the notion that FDA is flexible in terms of the quantity and quality of the clinical trials required for approval depending on the target indication of the new drug. Knowing FDA's current thinking on a particular drug type or indication is therefore imperative when designing potential clinical studies for a new drug.

Clinical trials are very expensive, and therefore it is in the sponsor's best interest to be sure the clinical trial design is not larger or more elaborate than necessary. Conversely, a sponsor should make sure that the proposed clinical trial presented is sufficient; lest FDA recommend something in addition that the sponsor cannot or does not want to complete. Trying to walk this fine line is not an easy task, and sponsors should work with their regulatory department or seek out regulatory consultants so that they can be sure they are well-versed on the clinical trial design and other regulatory requirements of products with similar indications before designing, presenting, and carrying out their regulatory strategy for their new drug product.

If you have any questions or thoughts on this blog post or others, please contact us today.

July 8, 2022

What is an Orphan Drug Designation? The Orphan Drug Designation (ODD) program in both the United States (U.S.) and European Union (E.U.) qualifies sponsors to receive potential incentives to develop...

February 7, 2017

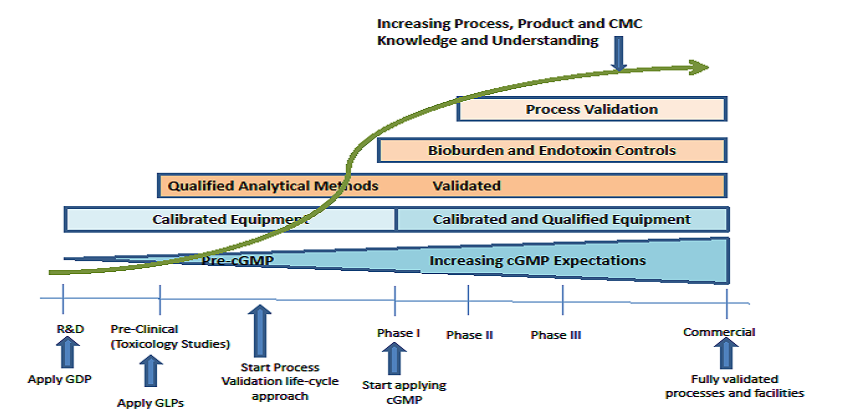

Phase-Appropriate Development and Application of Quality Systems in the Drug Development Process: The Parenteral Drug Association (PDA) recently published a revised version of Technical Report No....